The view from Bettina's front windows.

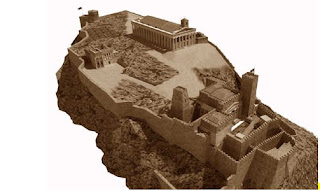

Ag. Giorgios, Nauplion, drawn by Leo von Klenze, 1834

This continues Brigitte Eckert contribution of excerpts from her translation of Bettina Schinas' letters from Greece in 1834-1835. Here Bettina writes with keen and gentle observation of her first weeks in Nauplion. Bettina was the daughter of Friedrich Carl von Savigny (1779-1861), prof. of Roman Law at the Berlin University and one of the developers of the new (Humboldt) university, and Gunda Brentano, from the Brentano family. She married one of her father's students, Konstantinos Schinas.

Bettina went with her husband to Nauplion in 1834, where they lived in a house at Ag. Giorgios (above), and then moved with the government to Athens in 1835. An letter from Bettina about Athens is here.

* * * * * *

To her parents, 2 November 1834:

First visit to Countess Armansperg who was very polite and kind, coming back home I found an invitation for the same evening. . .

The Armansperg house, 2010,

the first house in Nauplion to have a piano.

I must report about the evening at the Armanspergs. Beautiful rooms nicely decorated, filled with all kinds of people, diplomats, officers, dressed in Bavarian uniforms, as palikaria or French; also the ladies dressed French or Greek. The countess in mourning because of the Duke von Altenburg’s* death. She received me very kindly, complaining there would be no dancing because of the death. The daughters very pretty, very modest and polite, offered me conversation as they noticed I didn’t know anybody. The older played the piano later very skillful. The many rooms were crowded -- tea, ice cream, lemonades were offered. When the Countess saw me speaking with Kolettis, (I was standing up because he is so tall) she came and offered us 2 chairs next to each other so we could speak seated; the daughter played the piano, so we stopped our conversation. Ioannis Kolettis

Prime Minister, June 1834 - June 1835

To her parents, 5 November 1834:

Some hundred steps before our road met the big road to Argos we saw the king, 3 officers and 2 followers on horseback, and more 8 or 10 soldiers following.

Otto of Bavaria,

King of Greece 1832-1867

In Pronia (Nauplion suburb) we got off the horses and let the luggage be taken to town. At 4 ½ we reached our house facing Ag. Giorgos cathedral. Mr. Praidis (provisional Minister of Justice) who was still living in the rooms which the workers had finished did not expect us yet but moved out immediately. While he packed I waited in the room of the landlord, the archbishop who had watched us arriving came in, a colossal venerable man, indescribably warm towards S. [Bettina's husband] , and stayed with me though we couldn’t speak to each other.

Facing Ag. Giorgios, the front door of Bettina's house.

. . . Our lodging exceeds my expectations by far. At the front side facing the square a big room and a little boxroom, from there a big hall with a kitchen and larder at one side, at the end it meets in right angle a wide corridor with 3 spacious rooms; a 4th one longer than the corridor’s width, as big as our blue room at home, has 3 windows.

Ag. Giorgios and the L-shaped footprint of Bettina's house across the street.

To her parents, 31 December 1834

In front of the cathedral facing our house is, as I told you before, kind of a loggia, 3 doors open into the church, at one side is the bell tower, surely unique, like a top decoration of a cake, 2 bells hanging toneless between the little columns, a piece of string attached to them is just hanging down and tied to a nail, even small street urchins can reach it (to my despair). Behind the campanile rises a Turkish minaret of the same height, broken down to half size so as not to darken the campanile completely. A staircase which led to the minaret leans to one side of the campanile, and maybe for the sake of symmetry a second one has been added at the tower under the loggia of Orcagna,** which joins the first one behind the tower, and these attract the boys to run up and down. Next to this stair, in front of the side door, under the loggia lies the noble Ipsilanti whose memory is generally kept sacred. No stone, no sign of any kind indicates his tomb -- children play all kinds of games on it. Yesterday a priest emptied a big bucket of dirty water (from the construction works on the inside which are not yet finished) onto the tomb. Though there is so much more to do for the living it hurts that this tomb does not receive more respect. A splendid memorial would be unsuitable to the wishes of the dead, but some kind of sign is just missing. I did not know the man personally but I miss it when I look there or pass by.

To her parents, 7 December 1834:

. . . Using a large map you will see that the big half-moon shaped plain of Argos is bound at one end by Nauplia. The suburb of Pronia, very clean, pretty new houses, wide streets, lies at the foot of Palamides where the steep high bold rock slants towards the other mountains, it stretches to the mountains and the last houses are placed almost imperceptible higher. From Pronia to the by is the large drill-ground, up to a bridge which leads over a kind of moat to the gateway, the only one the town can have considering its location. The small door in the fortification which leads to a troublesome rocky footpath along the seashore can’t be considered a gateway.

On the water’s edge are many houses with kind of an embankment in front of them like a harbour, from which you can put to sea. The smell here is horrible because the water is low and the dirt of the town is brought here. Even now it smells marshy. S used to live here and each time I visit his sister and his former rooms I am glad that they are not mine. The drill-ground extends along the base of Palamidi, which has a front side aligned to town and sea. It is brusque, most picturesque, descending so steeply that an extremely arduous stair, supported fantastic by walls, leads upwards in a zigzag. A public garden about 80 steps wide lies between the drill-ground and Palamidi. From the steep rocky wall of Palamidi stretches like a spit of land, about half as high as Palamidi, the rock on which Itshkale (Acro-Nauplion) sits and the towns leans at and fills the space till the seashore.

Leaving the town by the bridge a wide footpath at the right side rises a bit between Palamidi and Itshkale, like a pass. This road leads up half the height of Palamidi for a rather long way where one can see on the right the clear sea, beyond the gulf the most beautifully shaped mountains one can think of, many layers of different forms, sizes, distances behind each other, each moment a new landscape by illumination. Many of these mountains are as high as being covered by snow two days after my arrival while the heat here was still going on, the snow staying for two days.

. . . The wealth of picturesque views existing here anyway is constantly increased by the changes of light and perspectives while moving along; this is the most significant when I walk through the hills at Pronia. Some rocky hills lie visible to their roots in the plain, like at Salzburg. The colour of hills and mountains (except of Palamidi, where the rock is brownish) gives at first sight the impression of unfertile and barren ground, a dead grey sometimes a bit yellowish. Several of these closer hills call the Lilienstein near Dresden to mind, rising gradually, then steep till the top where suddenly and wonderfully stratified completely naked grey rock appears and mostly ends flattened like the Lilienstein. Viewed from the plain the terrain seems to ascend regularly and it looks monotonous. But as soon as gaining a little height one finds unexpectedly deep and wild gorges torn by the waters in spring, now completely dried except some marshy spots where the young fish lie till they get washed down.

. . . One can see how all the mountains were cultivated, because the descending area is originally terraces built for fields or olive plantations, which only gradually flattened out. The ground is so fertile you need only a plough and seed without any further preparation to get an overflowing harvest. Heideck once picked an ear from a full field, it contained almost 100 grains, 3 ears growing from the same root, so 300-fold bears the corn without big effort and cost, fertilizer is hardly needed. With very thinly spread sheep’s dung the ground gets black and heavy like hotbed soil.

When H was Commander of Nauplia 1828 he found a significant part of the town in ruins - the buildings, not the streets, the sewerage marshy, weeds, thistles, thorny bushes lush at many places. The inhabitants, but only women and children as the men had been carried off by the war or were not back yet, lived in great numbers in straw huts like the plantation guards at home, all built close to each other, no pavement -- chicken, ducks, pigs and their dung next to the huts. When it rains here, the waters keep standing as there is no draining and it does not seep away; so the huts were surrounded by green mud ½ -1 foot high. H ordered the construction of the first houses of Pronia, just 4 walls, insisting the families move out of their huts, then tear them down and top the walls with a roof of these materials. In the beginning the women didn’t want to move of fear of the palikaria. But after they did the sewerage was opened, cleaned, the marshy placed were laid dry. In Pronia the people who moved in were mostly ill but they became well, as health generally improved gradually in Nauplia.

. . . The streets are paved, cobbled or macadamized except some spots filled with ruined remains of or left without buildings. Some newly built streets wide, straight, pretty friendly houses on both sides, more streets are older and therefore narrow, here stand new, renovated, old and partly collapsed buildings side by side. The new houses look like at home, not only roughcast but many painted like square stone blocks, decorations at the friezes etc.. In front of the windows, shutters or venetian blinds, painted green; windows with big panes, to open or to raise like we know them in Germany. Roofs not very high, with pediments and tiles, many houses roofed partly with a flat terrace where laundry can be dried. Balconies with beautiful wrought iron railings. The corridors and staircases are small in our terms. The staircases are made of stone or wood.

The doors don’t close, not even in new houses, probably because the wood is used too fresh or because the measurements of the doors coming ready-made from Trieste don’t fit exactly into the already built openings for the doors. At Armansperg’s house one can stick a hand through the doors. Thresholds don’t seem to be known to improve this trouble. I already decided my future doors will be closing one or another way. Stoves get set like in Italy -- at the beginning of winter next to a window, a pane is taken out and replaced by a piece of tin and the pipe stuck through it. Till today, Nov. 19th, I have no fire, not even with writing I don’t need to wear more than my brown merino woollen dress, no jacket, shawl, which are just bothersome. In traditional Greek pubs there is no stove, but a big copper coal machine in the middle of the room, like you know them from Italy. Floors are generally made of wood. The ceilings are also covered with wood (our ceilings are painted with oleo colour topped by a pattern of a different colour, though it is an old house, but belongs to Miaoulis, a Hydriot to whom cleanliness and neatness is essential.). With some Germans here you can find wallpapers, but generally walls are whitewashed or painted one colour. I gave you an idea of an old house and its furniture and fittings by the description of the Bey's house. Differences depending on poverty or wealth can be imagined.

. . . Some Greeks have an amazing mixture of poverty and splendour. The splendour is shown off with a silver salver for the preserved fruit sweets, a precious Turkish shawl, real pearls, diamonds etc. are remains of old wealth lost forever. A chest of drawers, solid mahogany, heavy bronze attached, marble cover, nothing else in an empty room or just surrounded by most simple thatched chairs; a precious modern table in front of a couch made of boards, covered by a mattress and cotton; or a big beautiful mirror in tasteful gold-painted frame at the same wall where single household appliances are hanging at nails because of the lack of drawers etc.; indicate the owner is not in poverty at all ( i. e. now or in the past has earned a pay which made the purchase possible, but which can end any day and put him vis à vis de rien). Otherwise he could not have bought the expensive things, but is as well evidence of the practical impossibility to buy here at the spot what is needed and reminds one in each moment that here more than anywhere else in the world patience is indispensable.

* Grandfather of King Otto of Greece.

* * * * * *

Copyright © Brigitte Eckert 2010.

Photographs by Brigitte Eckert.

SEE Ruth Steffen: Leben in Griechenland 1834–1835. Bettina Schinas, geb. von Savigny. Briefe und Berichte an ihre Eltern in Berlin. Verlag Cay Lienau, Münster 2002. ISBN 3-934017-00-2.