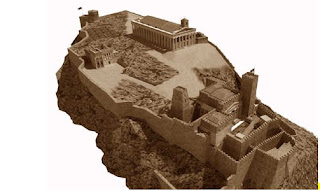

Detail from a view of the Acropolis, before 1680, from a drawing in Bonn.

Pierre A. MacKay spoke at the Archaeological Institute of America on 7 January about Evliya's view of the Parthenon and the Acropolis. He gives here one detail of that talk, his discovery of an extraordinary and previously unnoticed detail of early modern Athens written down by Evliya alone.

* * * * * *

There are three hundred houses built like those of Sheddad, fine masonry palaces, roofed all over with tile, houses like castles in their own right. They have no gardens, but from the arches over the seats in the windows and screened balconies of all the houses, the gardens and orchards of the plain, and all the cultivated fields and trellised melon patches can be seen.At least two of the houses in that image have balconies, most have arched windows, and the artist has indicated the tiled roof on one.

Evliya also notes that:

There are . . . hundreds of thousands of kinds of pictorial creation of marvels and wonders, images in the Frankish taste, which leave the viewer amazed and distraught, his brain in a boil, and his body without senses. The pupils of his dear eyes are dazzled and filled with tears, as if each of these representations were a living thing causing a dread confusion in a man’s mind. These images laugh and smile at the man who views them and some, which are depicted as being caught up in anger and rage, look off askance at a man.

Model of Frankish-Florentine palace in the Propylaea.

Evliya writes about houses in the lower town:

There are 7,000 tile-roofed houses, of both Muslims and Christians. They are sturdy houses, like castles with battlements and loopholes, and built completely of stone---there are no wooden houses or houses with earthen roofs or mud-brick walls, but only splendid houses with stone walls set with mortar and lime.

Evliya is quite clear that these houses are distinct from others in Greece, and in comparison with his descriptions of neighboring cities in regions both north and south of Athens, the specific features such as cut stone construction and battlements stand out sharply. Among the possible models for these Athenian houses, the closest similarities are with Florentine private residences of the 13th and 14th centuries. Cyriaco of Ancona would have stayed in these houses with Florentine friends on his visits to Athens.

The Duchy of Athens, officially established under Neapolitan sovereignty in 1395, remained in the hands of the Florentine Accaiuoli family until Mehmed II suppressed the duchy and removed the last duke, Francesco, in 1458. The duchy left a considerable cultural memory in western Europe ("A Midsummer Night's Dream," Chaucer's "The Knight's Tale" for two examples), perhaps more than it deserved, but we have had little evidence until now of the cultural influence of the Dukes on Athens. The Accaiuoli are known to have fostered close commercial relations with Florence, even when they were subject to rival powers, such as Venice, but this evidence suggests that they reinforced these relations by recruiting Florentines into Athens, probably by offering them significant privileges in the administration of the city and its territory.

The number of houses, whether on the acropolis or in the lower town is a typical Evliya exaggeration. Except in rare instances, numbers have a flavor, rather than a factual content in his style. The Accaiuoli seem to have got along rather well with Greeks, at least with better-off Greeks, so there is no reason to think that Greeks were disposessed to make room for Florentines. On the other hand, there is little reason for Greeks to have abandoned their own styles of housing to adopt a foreign style. Evliya remarked on the houses he found most interesting, and simply passed over the remainder which were probably in the majority.

The number of houses, whether on the acropolis or in the lower town is a typical Evliya exaggeration. Except in rare instances, numbers have a flavor, rather than a factual content in his style. The Accaiuoli seem to have got along rather well with Greeks, at least with better-off Greeks, so there is no reason to think that Greeks were disposessed to make room for Florentines. On the other hand, there is little reason for Greeks to have abandoned their own styles of housing to adopt a foreign style. Evliya remarked on the houses he found most interesting, and simply passed over the remainder which were probably in the majority.

House with double-fold windows

surviving in 1765-66, which can be compared with a typical Turkish house, below.

surviving in 1765-66, which can be compared with a typical Turkish house, below.

W. Pars, Museum Worsleyanum, 1794.

translated by Robert Dankoff.

Hello Diana,

ReplyDeleteAre you familiar with the painting in slide 24?

http://www.slideshare.net/iperrakis/1759-9940376

It is titled "Turkish house and the minaret of Fethiye mosque, unknown artist"

The ground floor is build around the remains of the Agoranomion in the Roman agora of Athens.

http://www.eie.gr/archaeologia/Gr/layout/images/05/zoom/6.jpg

The window, of course, is the reason of posting it here. I have no idea whether it was destroyed or saved after the excavations started, in 1837.

Regards,

Panos

That is a wonderful picture, and, no, I hadn't seen it before. Thank you!

ReplyDelete