In the summer of 1485, diplomat Giovanni Dario and the Ottoman court had to attend the hunting camp of the Sultan, Beyazid II. The weather was exceptionally hot, everyone had to live in tents, and cold water was unavailable. Dario was seventy-one and could not get neither doctor nor medicine for the pains in his chest. He wanted a taste of wine--impossible in Beyazid's ambit. He craved bed rest, but he was got out of bed to come observe the reception of the Egyptian ambassador.

It took all day. The ambassador had brought gifts, a lot of gifts, for the Sultan, who remained invisible. The pashas invited Dario into the shade of their pavilion--they were sitting on carpets on the grass, and they had a stool brought so he would not have to lower his aching, weighty body to the ground. Then the procession of gifts began.

In the summer of 1485, diplomat Giovanni Dario and the Ottoman court had to attend the hunting camp of the Sultan, Beyazid II. The weather was exceptionally hot, everyone had to live in tents, and cold water was unavailable. Dario was seventy-one and could not get neither doctor nor medicine for the pains in his chest. He wanted a taste of wine--impossible in Beyazid's ambit. He craved bed rest, but he was got out of bed to come observe the reception of the Egyptian ambassador.

It took all day. The ambassador had brought gifts, a lot of gifts, for the Sultan, who remained invisible. The pashas invited Dario into the shade of their pavilion--they were sitting on carpets on the grass, and they had a stool brought so he would not have to lower his aching, weighty body to the ground. Then the procession of gifts began.

The first was a great cat as large as a lion, with black spots: it had, he said, a terribilità. Then came six Arabian horses, the first with gilded saddle and trappings, and then three racing camels. "After this came the little presents," he wrote: three parrots in cages, four black eunuch boys, six swords, iron maces, battle axes, helmets, shields, saddles. Behind these came a procession of slaves, each one bearing two bolts of cloth--double weaves, scarlets, silks. All of these gifts were the preface to the Ambassador who advanced wearing green damask embroidered with gold and a cape of sable down to the ground. In July.

The ambassador was allowed fifteen minutes inside the imperial tent, then he was sent out to sit with the pashas and Dario. He directed that a large long scroll be cut open and read. As Dario said, "It was a very long reading." This was followed by a banquet of many dishes served on Chinese porcelain. He particularly liked a serving of vegetables with a lemon sauce.

That was the first day. The second day Dario was got out of bed again, this time for the reception of the Indian ambassador. He too had brought gifts, the first of them in a chest, and when Dario arrived at the pavilion, the ambassador and the pashas were rummaging in the chest, pulling out handfuls of jewels and passing them around. Dario was handed a dagger in a gold sheath ornamented with twenty-two large rubies, more little rubies, turquoises, and topped with a large pearl. Then the ambassador was allowed his fifteen minutes in the imperial tent. Again there was a procession of gifts--the grounds were full of slaves waiting their turn to march past, it was still very hot, and Dario noted that of all the diplomatic corps present, he was the only one invited to sit in the shade.

The pashas were making an inventory, and they reported 2600 bales of silk, eighty bales of scarlet cloth, more brocades, and then tray after tray laden with porcelain, followed by horse tails (these were Beyazid's symbol) cane lances, various Indian luxuries, and ending the procession, a single most beautiful red parrot.

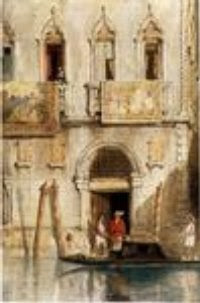

This parrot, or one like it, came back to Venice with Dario. It appears in Venetian paintings of the period, as in the Carpaccio detail above. What also came back, or the idea of it, or a Venetian painter had seen one in the East, was the great cat with black spots, its terribilità no longer in evidence here in this painting by Mansueti set in a Venetian house decorated like Dario's--this painting of a lonely Turk and his cheetah that has no place to run.

This parrot, or one like it, came back to Venice with Dario. It appears in Venetian paintings of the period, as in the Carpaccio detail above. What also came back, or the idea of it, or a Venetian painter had seen one in the East, was the great cat with black spots, its terribilità no longer in evidence here in this painting by Mansueti set in a Venetian house decorated like Dario's--this painting of a lonely Turk and his cheetah that has no place to run.