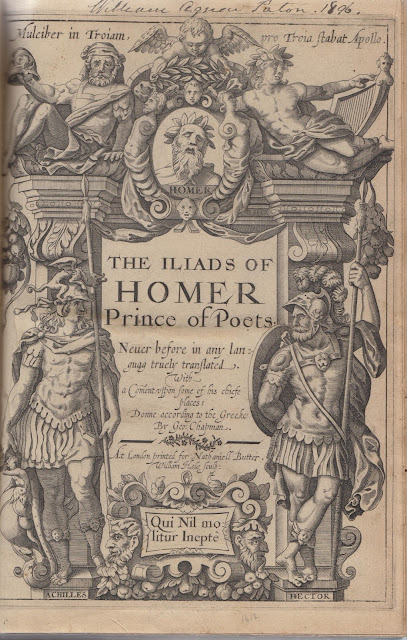

The Ottoman Fleet of Tarik-y Bayezid (ink and gold leaf on vellum)

16th century, which is early for Evliya.

This week, a section from Evliya Çelebi's Setyahatname, about a famous pirate and a battle at sea off Clarentza in 1668. The translation is by Pierre MacKay. The bolded headings in the text represent Evliya's red-ink marginal comments on the original manuscript

* * * * * *

Departing from [Vostitza], I went for 3 hours southwards to the Kamenítza river, which comes down from the Kalâvryta mountains and flows into the gulf at this spot. It is a small river, and crossing it on horseback, I came to the village of Mustafa Paşa. This is a great bequest trust for the mosque of Mustafa Paşa in Gebze, which is a day's journey away from Üsküdar. The tributary populace is all Albanians. Another 3 hours from there is the

village of Mertéza, which is a zeamet-class fief of the Commander of the Levy for Morea. It tributary populace is all Greeks. This village is at the skirts of the "Black Mountain" of Morea, where all the infidel frigates have little landing places in the forest. They hide here and capture travellers and passers-by, and then sail away. From this village we went into the limitless plain of Gastúni and passed by prosperous villages with mosques,

inns and great houses, and through gardens and orchards like the gardens of Irem, and so came to Glarénza).

Description of the entire castle of Glarénza

It was founded by the Bundukani Venetians. In Greek, Glarénza (Larence) means . . ., and that is the reason for the name.

In the year . . ., it was a conquest of Sultan Beyazid the Saintly, but the conquest was made with great toil and suffering, and since the castle was largely useless he demolished it in several places. Since Patras and Chlemútsi are both close by, he left this castle in ruins although, when it was still standing, the saying goes that on the whole island of Morea there was no stronger nor more thickly populated | fortress. There are huge great pieces of the wall fabric lying about in many places, and it could easily be repaired if there were any occasion for it. It was a stout, five-sided fortress on the seashore with freshwater sources and two harbors where one may lie safe from all eight winds without fear or apprehension. The Algerian privateers, when they are cruising at sea looking for a prey, come in to cast anchor and lie at this harbor of Glarénza whenever they perceive the hill of Chlemútsi.

Witness of a seafight, in a tale worthy of future remembrance

Your poor and humble servant hid my horses away in the hills and came back on foot with two of my servants to Glarénza, where the three of us concealed ourselves in a corner of the great field of ruins, and inspected the island of Cephalonia, out in the gulf, with a telescope.This island is under the domination of the Venetian Franks, and while we were making a survey of all the details that were clearly visible through the telescope--the towers and wallsof the castle, the landing places, and the infidels themselves, both great and small--eight Muslim frigates appeared, flying green standards, with pennants waving in the wind.

It happened that certain of our warrior heroes from Naupactus, namely Dorak Bey and Mısırlı Oğlu, were bringing their ships back from an expedition when ten frigates emerged from the harbor of the afore-mentioned infidel castle of Cephalonia and fell unexpectedly on Dorak Bey's squadron. The ships of Islam came into close engagement with the infidel frigates all across the face of the sea, and there was a huge battle. Your humble servant could not endure the rain of spent cannon and rifle shot falling in the ruins of Glarénsa castle, and retired to hide in a corner, but certain it is that our brave heroes made a fine, vigorous fight of of it.

Now our ships were returning from an expedition, and all eight of them were crammed full of infidel captives and loaded down with immeasurable amounts of tightly packed booty acquired as the spoils of war. The crews themselves were battle-ready, but the ships were not properly loaded for an engagement. The ten galleys of the enemy, on the other hand, were first-rate ships, fully armed and not loaded down. Moreover they had caiques and rowing boats coming up behind to help. Our ships of the Muslim fleet, therefore, | became apprehensive about the close-packed cargo of infidel prisoners, fearing that they might have a chance to raise their heads against us in the course of the fight. As a result, all eight Muslim frigates broke off from the engagement and as soon as they were free cried, "Full speed ahead!" and pulled on the oars with all their strength, heading in to shut themselves up in the harbor of Glarénza castle, from which we had been watching them.

When they saw my poor self there, the heroes were delighted, and in the twinkling of an eye they had unloaded all the booty, the heavy cargo and the infidel prisoners with their hands bound behind their necks. They turned this all over to me, and I brought down my slaves and my horses, and mounted my own horse to stand guard over the infidel captives while | I sent one of my slaves up to a village in the hills to tell the tributary populace to come down here fully armed. As soon as they arrived, we massed the infidel captives into the middle of our party, loaded them up with all the heavy cargo and marched them up away from the castle ruins and into the hills where we left them safe.

Meanwhile, Dorak Bey, with his eight frigates now free and unencumbered, selected five hundred of the youngstalwarts who were gathering round from all four sides to look at the battle and tumult, and filled his ships with them. Then he sailed back out of Glarénza harbor again and pulledahead at full speed against the infidels. The noise and tumult of the close-fought melée and the exchange of fire was heard all the way to Patras and Chlemútsi, and young warriors rushed along the roads to get into ships in time to bring aid to the hero, Dorak Bey. He then took up a position in the middle of the ten enemy frigates, and filled the gun-crews tending the infidel cannon with so much lead and cannon-shot that he made prizes of eight of the enemy ships all at once. The other two turned about and ran back into the harbor of Cephalonia.

Glory to God--Dorak Bey had now conquered eight more ships with his eight and had madeprisoners of all their infidel crews, as well as capturing a proportional amount of cargo, weapons and ordnance materiel. He turned back into Glarénza harbor, therefore, and whenhe dropped anchor, I brought back the prisoners and booty that were up in the hills and turned them over once again to Dorak Bey. At this, the hero Dorak Bey, Mısırlı Oğlu, and the other officers and sea-captains gave me three prisoners in payment for my services, along with two European boy-slaves and a purse of silver thalers. Then the whole expedition reboarded the sixteen ships and after turning the crucifix idols upside down on all he eight infidel ships, they fired a joyous salute of cannon and rifle fire, let out their sails and set out straightaway with the day's prizes for the castle of Naupactus.

So your humble servant was accidentally the witness of such a sea-fight, and God, in His Greatness, presented me with five captives and a purse of silver. For it was God who rewarded me thus, in that I, a traveller by land, was granted a present of booty taken at sea. Actually, I sent the five captives I had been given to accompany the remaining prisoners of Dorak Bey and the other heroes who were going to Naupactus, and directed one of my slaves to send them on from there to Zekeriya Efendi in Corinth, along with a letter telling him to sell them. So they went off to Naupactus and I went on southwards, and in three hours climbed up to Chlemútsi.